Introduction

Currently the exponential advance of technology is no longer a surprise, but rather an inherent characteristic of the modern world. Even though this evolution constantly enhances devices, it does not do so in a homogeneous way, creating a world where the distribution of computational power is asymmetric. In this scenario, the ability to safely delegate hard computations to a powerful third party becomes very attractive. Studies in Verifiable Computation address this problem seeking to provide a series of important guarantees. The most important and intuitive one is that the verification must be easier than the computation of the function delegated (if this was not the case, the client should just perform the computation himself). Depending on the scheme implemented, other interesting qualities may be provided, such as public verification (in contrast, some settings may require a designated verifier that is trusted with secret information).

Some of the most common settings that make use of VC involve a weak client (such as a mobile device) that needs to compute an expensive function, making use of a powerful server to do so. Among the concrete applications we can list cloud computing, grid computing and distributed computing. In particular, the scheme proposed by Pinocchio provides interesting characteristics. It is not only efficient when compared to previous literature, but also has room to implement a zero-knowledge verification and requires no designated verifier. It makes heavy use of Quadratic Arithmetic Programs (QAP) and cryptographic primitives that will be detailed in the following sections. The particular use for QAPs stems from the fact that Turing Machines can be expressed as these circuits (which only contain sums and multiplications), making them a good way to represent the computation to be performed.

Background

Verifiable Computations

The main idea of Pinocchio is to provide a effective framework for verifiable computation. But what really is verifiable computation?

A public verifiable computation scheme $\mathcal{VC}$ consists of a set of three polynomial-time algorithms (KeyGen, Compute, Verify) defined as follows.

$(\text{EK}_F, \text{VK}_F) \leftarrow \text{KeyGen}(F, 1^\lambda)$: Outputs a public evaluation key $\text{EK}_F$ and a public verification key $\text{VK}_F$.

$(y, \pi_y) \leftarrow \text{Compute}(\text{EK}_F, u)$: Outputs $y \leftarrow F(u)$ and a proof $\pi_y$.

$\{0, 1\} \leftarrow \text{Verify}(\text{VK}_F, u, y, \pi_y)$: Uses $\text{VK}_F$ and outputs whether $F(u) = y$.

In other words, a Public Verifiable Computation scheme (VC scheme for short) allows us to compute any function $F$ on input $u$ and, then, publicly verify that $F(u)$ is indeed equal to $y$. We shall also utilise the following definitions for correctness, security and efficiency:

Correctness: For any function $F$, and any input $u$ to $F$, if we run $(\text{EK}_F, \text{VK}_F) \leftarrow \text{KeyGen}(F, 1^\lambda)$ and $(y, \pi_y) \leftarrow \text{Compute}(\text{EK}_F, u)$, then we always get $1 = \text{Verify}(\text{VK}_F, u, y, \pi_y)$.

Security: For any function $F$ and any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary $\mathcal{A}$, $\text{Pr}[(\hat{u}, \hat{y}, \hat{\pi_y}) \leftarrow \mathcal{A}(\text{EK}_F, \text{VK}_F) \colon F(\hat(u) \neq \hat{y} \; \text{and} \; 1 = \text{Verify}(\text{VK}_F, \hat{u}, \hat{y}, \hat{\pi_y})] \leq \text{negl}(\lambda)$.

Efficiency: KeyGen is assumed to be a one-time operation whose cost is amortized over many calculations, but we require that Verify is cheaper than evaluating $F$.

Note that when specifying the security of a VC scheme, we allow for and adversary to be able to fake a computation that did not occur in reality. However, by the correctness of the scheme, a computation that happened will never return 0 after a Verify function call.

It is worth mentioning that many previous VC schemes were not publicly verifiable, which increased the attack surface since a leak of the verification key, $\text{VK}_F$, could lead to attacks on the system. A public scheme avoids these issues.

The whole idea of Pinocchio is to build such a VC scheme that works securely and efficiently. To this end, we will use the notion of Quadratic Arithmetic Programs, which will be defined and explained in the next section.

Quadratic Arithmetic Programs

Since we are interested in functions $F$ that can be expressed with sums and multiplications, a great way to represent such functions is by an arithmetic circuit. Such circuit is made up from nodes (or gates) that represent operations (sums or multiplications) and a set of input and output wires. Each node is connected with wires that carry values from a field $\mathbb{F}$. A way to encode (represent) such circuit is by using a Quadratic Arithmetic Program (QAP).

We will also need the concept of a QAP that computes a function $F$.

Suppose $F$ is a function that takes as input $n$ elements of $\mathbb{F}$ and outputs $n^\prime$ elements, for a total of $N = n + n^\prime$ I/O elements. Then, we say that $Q$ computes $F$ if:

$(c_1, \dots, c_N) \in \mathbb{F}^N$ is a valid assignment of $F$’s inputs and outputs if, and only if, there exist coefficients $(c_{N + 1}, \dots, c_m)$ such that $t(x)$ divides $p(x)$, where:

$$ p(x) = v(x) w(x) - y(x) $$and

$$ v(x) = v_0(x) + \sum_{k = 1}^{m} c_k v_k(x) $$$$ w(x) = w_0(x) + \sum_{k = 1}^{m} c_k w_k(x) $$$$ y(x) = y_0(x) + \sum_{k = 1}^{m} c_k y_k(x) $$In other words, there must exist $h(x)$ such that $t(x) h(x) = p(x)$. The size of $Q$ in this case is $m$ and its degree is the same as $t(x)$’s degree.

Remember that a QAP is only a way to represent an arithmetic circuit. Let us, then, show how to build a QAP from a circuit C. First, we choose an arbitrary root $r_g \in \mathbb{F}$ for each multiplication gate, $g$, in C. Then, our target polynomial $t(x)$ will be:

$$ t(x) = \prod_{g \in C} (x - r_g) $$Thus, the roots of $t$ are precisely the roots we specified for the multiplicative gates. Now, we assign the index $k \in [n] = \{1, \dots, n\}$ to each of the $n$ inputs of the circuit and the index $k \in [n + 1, m] \subset \mathbb{N}$ to each of the outputs of multiplication gates $g \in C$.

Finally, we let $v_k(x)$, $w_k(x)$ and $y_k(x)$ encode the left input, right input and output of each gate, respectively. The way the encode works is as follows: if $k$-th wire is a left input of gate $g$, then $v_k(r_g) = 1$. Otherwise, $v_k(r_g) = 0$. The same goes for $w_k(x)$ and $y_k(x)$.

This way, we just defined $\mathcal{V}$, $\mathcal{W}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$ from the definition of the QAP.

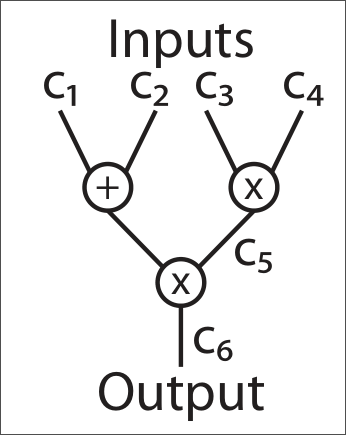

Let $F(c_1, c_2, c_3, c_4) = (c_1 + c_2) \times (c_3 \times c_4)$ be a function of 4 inputs and 1 output. The following figure shows an arithmetic circuit that computes this function.

Let us say that the multiplication gate between $c_1$ and $c_2$ is $r_5$, its output wire is $c_5$ and $c_6$ is the output of the last multiplication gate, which is $r_6$. Below are some evaluations of polynomials from $\mathcal{V}$, $\mathcal{W}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$:

$v_1(r_5) = 0$; $v_1(r_6) = 1$.

$v_2(r_5) = 0$; $v_2(r_6) = 1$.

$w_3(r_5) = 0$; $w_3(r_6) = 0$.

$w_4(r_5) = 1$; $w_4(r_6) = 0$.

$y_5(r_5) = 1$; $y_5(r_6) = 0$.

$y_6(r_5) = 0$; $y_6(r_6) = 1$.

We can also say that $t(x) = (x - r_5) (x - r_6)$.

Following our definitions of $\mathcal{V}$, $\mathcal{W}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$, it is easy to see that

$$ v(r_g) w(r_g) = \left( \sum_{k \in I_\text{left}} c_k \right) \left( \sum_{k \in I_\text{right}} c_k \right) = c_g y_k(r_g) = c_g, $$when considering a particular multiplication gate $g$ and its root $r_g$. Thus, we have $p(r_g) = 0$ for every multiplicative gate. This means that we can check whether $t(x)$ divides $p(x)$ simply by checking the evaluation of $p(x)$ at the roots of the multiplication gates. Note that in order for $p(x)$ to have roots at the points $r_g$, all $c_i$, $i \in [m]$, must be computed, which in turn include the outputs of $F$

Bilinear Groups

The last idea we need before getting into Pinocchio’s implementation is the concept of bilinear groups.

The special property we are looking for is the bilinearity of $e$.

Suppose $|\mathbb{G}_1| = |\mathbb{G}_2| = |\mathbb{G}_T| = Q$, $g_1 \in \mathbb{G}_1$ generates group $\mathbb{G}_1$ and $g_2 \in \mathbb{G}_2$ generates group $\mathbb{G}_2$. Then, for all $a, b < Q$, we have that

$$ e(g_1^a, g_2^b) = e(g_1, g_2)^{ab}. $$The main thing to keep in mind is what happens to the exponents $a$ and $b$ during the mapping: they are multiplied. Usually, we have $\mathbb{G}_1, \mathbb{G}_2 \neq \mathbb{G}_T$, so the output of the function cannot be used again in $e$ as input.

From the property of bilinearity, we can derive several other useful properties. We highlight two of them that we will need later on:

$e(g_1^a, g_2^b) = e(g_1, g_2)^{ab} = e(g_1^{ab}, g_2)$.

If $c < Q$, then $\frac{e(g_1^{ab}, g_2)}{e(g_1^c, g_2)} = \frac{e(g_1, g_2)^{ab}}{e(g_1, g_2)^{c}} = e(g_1, g_2)^{ab - c} = e(g_1^{ab - c}, g_2)$.

Schwartz-Zippel lemma

The Schwartz-Zippel lemma is a very useful mathematical tool to check for the equality of two polynomials efficiently. The lemma is given below.

Let $f(x) \in \mathbb{F}[x]$ be a non-zero polynomial of degree $d \geq 0$. Then, if we sample $s$ uniformly at random from $\mathbb{F}$, it holds that

$$ \text{Pr}[f(s) = 0] \leq \frac{d}{|\mathbb{F}|} $$The key consequence of the lemma is that the probability of two polynomials of degree less than or equal to $d$ evaluating to the same value at a random point if $\mathbb{F}$ is also bounded by $\frac{d}{|\mathbb{F}|}$. In other words, if two polynomials, $p_1$ and $p_2$, are equal at a random point $s \in \mathbb{F}$, the probability that $p_1 \neq p_2$ is at most $\frac{d}{|\mathbb{F}|}$, which is unlikely if the field $\mathbb{F}$ is big enough.

All this to say that we will assume polynomials $p_1(x)$ and $p_2(x)$ are equal for all $x \in \mathbb{F}$ if they are equal at a random point.

Pinocchio

Now we have all the theoretic background we need to implement Pinocchio. Just a small recapitulation: our goal is to build a generic VC scheme that computes any function $F$ that can be written with sums and multiplications. To this end, we will describe Pinocchio’s implementation for each of the functions specified in the definition of a VC scheme.

Key generation

The KeyGen function takes as input the function $F$ and the security parameter $\lambda$ and it outputs the evaluation key $\text{EK}_F$ and the verification key $\text{VK}_F$. The first step is to convert $F$ into an arithmetic circuit $C$ and, then, build the corresponding QAP $Q = (t(x), \mathcal{V}, \mathcal{W}, \mathcal{Y})$ of size $m$ and degree $d$. Also, let $I_\text{mid} = \{N + 1, \dots, m\}$ be the non-IO-related indices, $e \colon \mathbb{G} \times \mathbb{G} \to \mathbb{G}_T$ be a non-trivial bilinear map, and $g \in \mathbb{G}$ be a generator of $\mathbb{G}$.

Now, choose $r_v, r_w, s, \alpha_v, \alpha_w, \alpha_y, \beta, \gamma \xleftarrow{R} \mathbb{F}$ and set $r_y = r_v r_w$, $g_v = g^{r_v}$, $g_w = g^{r_w}$ and $g_y = g^{r_y}$. Here, $s$ is a secret and random value that will be used in conjunction to the Schwartz-Zippel lemma later. Finally, we define the evaluation and verification keys as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} \text{EK}_F = (\quad &\{g_v^{v_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, &&\{g_w^{w_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, &\{g_y^{y_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, \\ &\{g_v^{\alpha_v v_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, &&\{g_w^{\alpha_w w_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, &\{g_y^{\alpha_y y_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}}, \\ &\{g^{s^i}\}_{i \in [d]}, && \{g_v^{\beta v_k(s)} g_w^{\beta w_k(s)} g_y^{\beta y_k(s)}\}_{k \in I_\text{mid}} \quad) \end{align*} $$$$ \text{VK}_F = (g^1, g^{\alpha_v}, g^{\alpha_w}, g^{\alpha_y}, g^{\gamma}, g^{\beta \gamma}, g_y^{t(s)}, \{g_v^{v_k(s)}, g_w^{w_k(s)}, g_y^{y_k(s)}\}_{k \in \{0\} \cup [N]}) $$Computation

The Compute function takes as input the evaluation key, $\text{EK}_F$, and the input of $F$, $u$, and outputs $(y, \pi_y)$ where $y = F(u)$ and $\pi_y$ is a proof that the computation was indeed executed.

To do so, the worker simply evaluates $F(u)$ using the circuit $C$ and stores the output in $y$. By doing it, the worker is also able to compute all $c_i$, $i \in [m]$, inside the circuit. Since it knows the QAP $Q$ as well, the worker can calculate $h(x)$ by doing the polynomial division below.

$$ \frac{p(x)}{t(x)} = h(x) = h_0 + h_1 x + h_2 x^2 + \dots + h_d x^d $$Now, it is easy for the worker to compute $v_\text{mid}(s)$, $w_\text{mid}(s)$, and $y_\text{mid}(s)$ using the properties of exponentiation.

$$ \prod_{k \in I_\text{mid}} \left( g_v^{v_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} = g_v^{\sum_{k \in I_\text{mid}} c_k v_k(s)} = g_v^{v_\text{mid}(s)} $$$$ \prod_{k \in I_\text{mid}} \left( g_w^{w_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} = g_w^{\sum_{k \in I_\text{mid}} c_k w_k(s)} = g_w^{w_\text{mid}(s)} $$$$ \prod_{k \in I_\text{mid}} \left( g_y^{y_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} = g_y^{\sum_{k \in I_\text{mid}} c_k y_k(s)} = g_y^{y_\text{mid}(s)} $$The same idea can be extended to $\alpha_v v_\text{mid}(s)$, $\alpha_w w_\text{mid}(s)$, $\alpha_y y_\text{mid}(s)$ and $g_v^{\beta v_\text{mid}(s)} g_w^{\beta w_\text{mid}(s)} g_y^{\beta y_\text{mid}(s)}$. Finally, we determine $h(s)$:

$$ \prod_{i \in \{0\} \cup [d]} \left( g^{s^i} \right)^{h_i} = g^{\sum_{i \in \{0\} \cup [d]} h_i s^i} = g^{h(s)} $$Thus, our proof $\pi_y$ is as follows.

$$ \begin{align*} \pi_y = (\quad &g_v^{v_\text{mid}(s)}, &&g_w^{w_\text{mid}(s)}, &g_y^{y_\text{mid}(s)}, \\ &g_v^{\alpha_v v_\text{mid}(s)}, &&g_w^{\alpha_w w_\text{mid}(s)}, &g_y^{\alpha_y y_\text{mid}(s)}, \\ &g^{h(s)}, &&g_v^{\beta v_\text{mid}(s)} g_w^{\beta w_\text{mid}(s)} g_y^{\beta y_\text{mid}(s)} \quad) \end{align*} $$Verification

Once the worker computes our function, we need to verify that $F(u)$ is actually $y$. The function Verify takes as input $\text{VK}_F$, $u$, $y$ and $\pi_y$ and outputs $0$ or $1$. To do so, we perform three checks using $\pi_y$.

Divisibility check: First, with the values from $\text{VK}_F$, the client computes the following three values:

$$ g_v^{v_\text{io}(s)} = \prod_{k \in [N]} \left( g_v^{v_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} $$$$ g_w^{w_\text{io}(s)} = \prod_{k \in [N]} \left( g_w^{w_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} $$$$ g_y^{y_\text{io}(s)} = \prod_{k \in [N]} \left( g_y^{y_k(s)} \right)^{c_k} $$Now, using $g_v^{v_0(s)}$, $g_v^{v_\text{io}(s)}$ and $g_v^{v_\text{mid}(s)}$, one can compute $g_v^{v(s)}$. The same goes to $g_w^{w(s)}$ and $g_y^{y(s)}$.

Finally, the client checks the following equality:

$$ e(g_v^{v(s)}, g_w^{w(s)}) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g_y^{t(s)}, g^{h(s)}) e(g_y^{y(s)}, g) $$What the above equation tells us is whether $r_v v(s) r_w w(s) = r_y t(s) h(s) + r_y y(s)$, which implies that $p(s) = v(s) w(s) - y(s) = t(s) h(s)$. If this is true, we know that $\frac{p(x)}{t(x)} = h(x)$ by the Schwartz-Zippel lemma. Hence, the divisibility check.

Coefficients check: We check if the same coefficients $c_i$, $i \in [m]$ were used across all computations. To this end, the client checks the following:

$$ e(g^Z, g^\gamma) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g_v^{v_\text{mid}(s)} g_w^{w_\text{mid}(s)} g_y^{y_\text{mid}(s)}, g^{\beta \gamma}) $$where $g^Z = g_v^{\beta v_\text{mid}(s)} g_w^{\beta w_\text{mid}(s)} g_y^{\beta y_\text{mid}(s)}$. It is easy to see that by choosing a good $\beta$, the above equality holds only if all $c_i$ are consistent.

Span check: We check if the multiplication of the functions $v$, $w$ and $y$ by their respective alphas ($\alpha_v$, $\alpha_w$ and $\alpha_y$) does not overwhelm the spans of $\mathcal{V}$, $\mathcal{W}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$. This can be done by checking the three equalities that follow.

$$ e(g_v^{\alpha_v v_\text{mid}(s)}, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g_v^{v_\text{mid}(s)}, g^{\alpha_v}) $$$$ e(g_w^{\alpha_w w_\text{mid}(s)}, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g_w^{w_\text{mid}(s)}, g^{\alpha_w}) $$$$ e(g_y^{\alpha_y y_\text{mid}(s)}, g) \stackrel{?}{=} e(g_y^{y_\text{mid}(s)}, g^{\alpha_y}) $$With these three checks (divisibility, coefficients and span) we can conclude that $F(u) = y$.

Security

As to its security, the Pinocchio scheme relies on cryptographic primitives to keep malicious servers from providing fake proofs of the computation performed. In particular, it makes use of the Diffie-Hellman assumptions by expressing the values of the functions in the exponent.

The $d$-PKE, also called $d$-Bilinear Diffie-Hellman Exponent ($d$-BDHE) assumption goes as follows:

Given elements of the form $g^a, g^{a^2}, g^{a^3}, \dots$, it is hard to derive $e(g, g)^{a^{d - 1}}$

Moreover, it makes use of the $2q$-Strong Diffie-Hellman assumption ($2q$-SDH).

The $2q$-SDH problem goes as follows:

The adversary is given elements $(g, g^a, g^{a^2}, \dots, g^{a^q})$.

The adversary must compute $(g^\frac{1}{a + x}, x)$ for some $x$ without knowing $a$.

The assumption states that this is a hard problem.

It is also important to define the $q$-Parallel Diffie-Hellman ($q$-PDH) assumption, that states that it is hard to solve a parallel version of the DH problem, or, in other words, multiple DH problems simultaneously.

By using these two assumptions simultaneously, we force an adversary to either break the $q$-PDH by not using the same linear combinations in the exponent of the terms provided or to break the $2q$-SDH by computing elements that fail the divisibility test.

Implementation of boolean gates

The QAP used in Pinnochio’s VC scheme is defined over $\mathbb{F}_p$, where $p$ is a large prime.

Even though this scheme gives us an efficient way to compute functions that do additions and multiplications modulo $p$, it provides no obvious way to express some boolean operations, such as $a \geq b$. On the other hand, given $a$ and $b$ as bits, comparison is easy.

To solve this problem, Pinocchio’s authors designed an arithmetic split gate that translates any wire $a \in \mathbb{F}_p$, known to be in $[0, 2^k - 1]$, into $k$ binary output wires.

With such output wires, it is possible to easily implement boolean functions. Below, we list some examples of functions that can be implemented using two binary values and arithmetic operations:

$\text{NAND}(a, b) = 1 - ab$.

$\text{AND}(a, b) = ab$.

$\text{OR}(a, b) = 1 - (1 - a)(1 - b)$.

It is also worth mentioning that these boolean operations can be implemented using only 1 multiplication, so each of them costs only 1 to the degree and size of the QAP. Furthermore, the recombination of binary wires into a value $a \in \mathbb{F}_p$ is free, because it consists only of multiplications by constants and additions.

Results

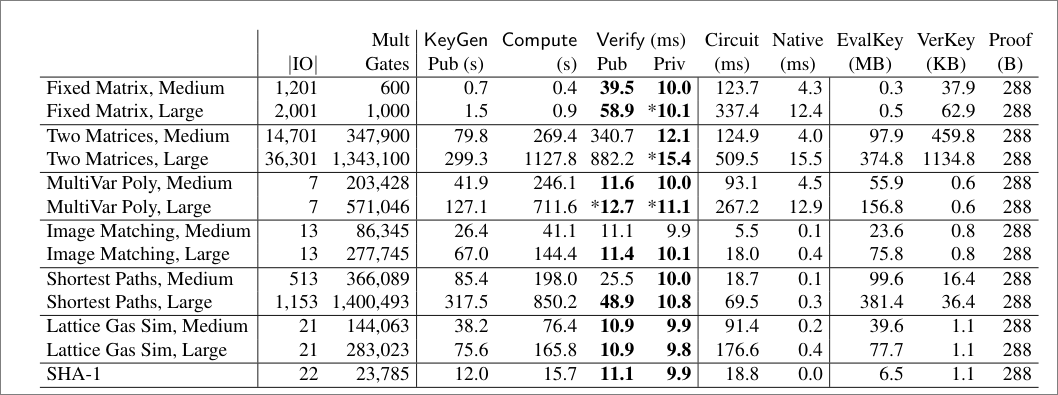

Pinocchio’s scheme turns out to be efficient and practical for many use cases. The authors of Pinocchio’s paper ran a number of tests on some real-world problems in order to test the performance of the scheme.

To this end, Parno et al. built a C-to-arithmetic-expression compiler called qcc. With this tool, they were able to write C code and then compare the execution times of Pinocchio and the native code.

The authors tested a total of 7 applications using Pinocchio:

Multiplication of a matrix $M \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ and a vector $A \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

Multiplication of two matrices $n \times n$.

Evaluation of a multivariate polynomial with $k$ variables and degree $m$ (with $k = 5$ and $m = 10$, there are more than $600000$ coefficients).

An image matching algorithm that takes as input an image and a image kernel and outputs the minimum difference and the point where it occurs.

Floyd-Warshall’s algorithm for shortest paths.

A Lattice-Gas Cellular Automata that converges to Navier-Stokes.

SHA-1 algorithm.

The table below shows the Pinocchio’s results when executing each of the 7 problems. Values in bold represent verification times that are cheaper than computing the circuit locally. The stars (*) indicate verification is cheaper than native execution.

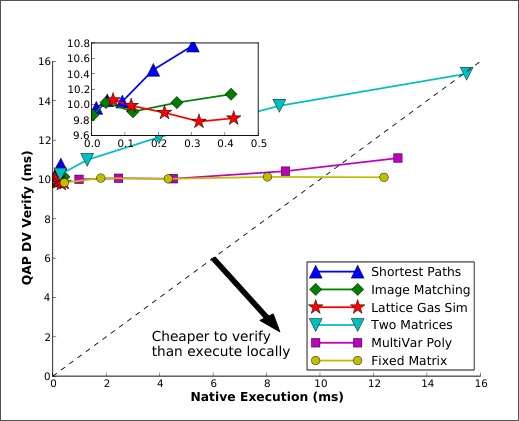

The following graph shows with more details the comparison between the verification cost and the native execution cost.

It is clear that for sufficiently large parameters, the computations with Pinocchio may be faster than the native execution.

Comparison to other works

As previously stated, Pinocchio presents efficiency gains when compared to other alternatives in literature.

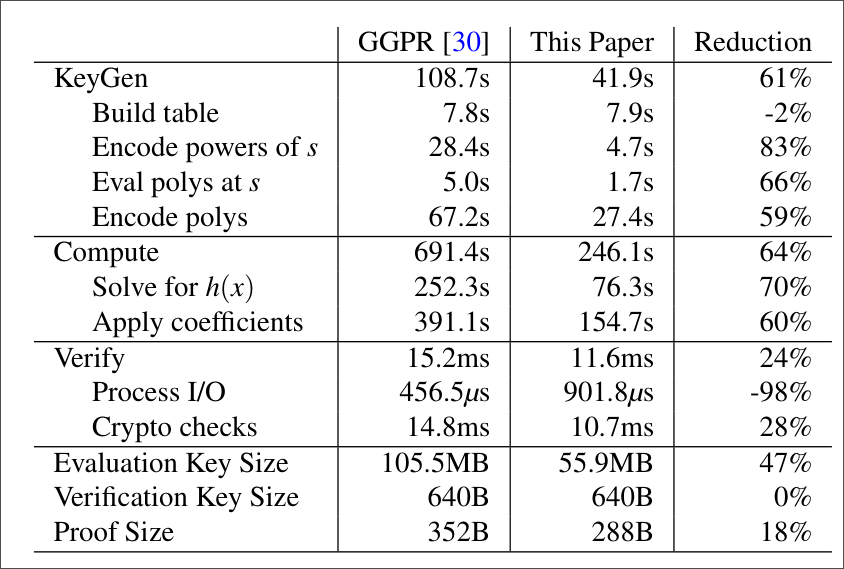

In particular, when put side by side with GGPR, it uses QAPs whose degree is over three times shorter. This happens due to a relaxation in the assumptions made over the QAP’s nature.

GGPR requires the QAP to be strong, which means that all the polynomial families share the same constants $c_i$. While this is not true for every instance, it has been proven that a regular QAP can be “strengthened” and become strong.

However, the setback of this procedure is that it more than triples the degree of the QAP and, therefore, the computation performed in the scheme. Pinocchio’s advantage resides in the fact that it does not make such assumptions, allowing us to use weak QAPs.

Another advantage over GGPR is that its proof $\pi_y$ has 9 elements, whereas Pinocchio only has 3. This reduction significantly increases the performance of the calculations, especially in the KeyGen function.

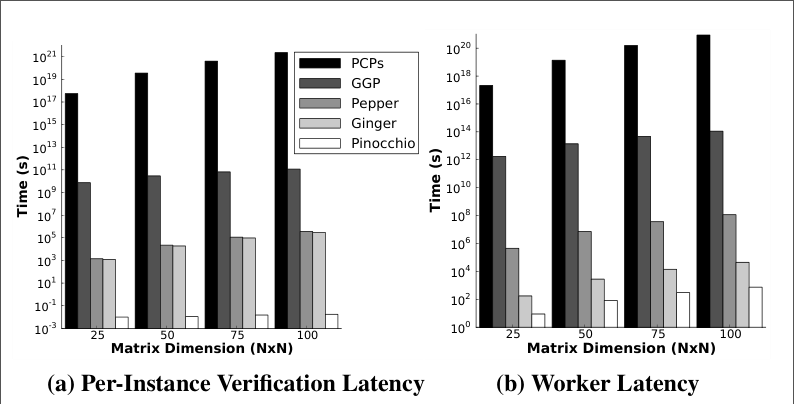

The graph below shows how Pinocchio compares to previous works of VC in the problem of multiplying two matrices of dimensions $N \times N$. Note that the y-axis is in logarithmic scale.

The table below compare Pinocchio and GGPR using a problem of evaluating multivariate polynomials.

There were also other works that actually improved Pinocchio’s functionality. Geppetto is one example: Costello et al. identified some problems in Pinocchio’s approach to proof build in the worker. According to them, computing $\pi_y$ costs about 3 to 6 orders of magnitude more than the evaluation of $F(u)$.

To solve this, they implied a new notion of Multi-QAPs to share states between or within computations and were able to substantially reduce the prover’s computation time (up to 1169 times in some cases).

On top of that, Geppetto was able to produce what they call “energy-saving circuits”. Essentially, they found a way to disable parts of the circuit in regions containing branches. While Pinocchio’s approach is to evaluate expressions and then decide the final result based on conditional variables, Geppetto can evaluate the branch beforehand, so that the circuit is only evaluated in the right regions.

Conclusion

With the help of Pinocchio, we were able to construct a Public Verifiable Computation Scheme, making use of QAPs. This construction allows us to outsource the computation of any function $F$ made from additions and multiplications to a possibly untrusted worker and, then, verify the computations done. The process of key generation and verification are also very fast when compared to previous approaches.

Moreover, by the usage of the Schwartz-Zippel lemma, the scheme’s proof of computation has a size of 288 bytes, regardless of the size of the computation. The creation of the split gate also makes it possible to implement functions that are not only arithmetic, but that can be expressed in terms of boolean operations.

However, there are some setbacks with the techniques used. Namely, the overhead of proof construction by the worker is still very high and the great size of parameters needed to make the scheme actually useful. Geppetto was able to solve some of these issues, but the scheme is still far from perfect.

All in all, the results of this work are promising. They represent a great advancement when compared to previous papers and a step towards total verifiable computation.

References

Parno, B., Howell, J., Gentry, C., & Raykova, M. (2016). Pinocchio: Nearly practical verifiable computation. Communications of the ACM, 59(2), 103-112.

Szabo, N. (2007, September 02). Bilinear Group Cryptography. Unenumerated. https://unenumerated.blogspot.com/2007/09/bilinear-group-cryptography.html

Gennaro, R., Gentry, C., Parno, B., & Raykova, M. (2013). Quadratic span programs and succinct NIZKs without PCPs. In Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2013: 32nd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Athens, Greece, May 26-30, 2013. Proceedings 32 (pp. 626-645). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Costello, C., Fournet, C., Howell, J., Kohlweiss, M., Kreuter, B., Naehrig, M., … & Zahur, S. (2015, May). Geppetto: Versatile verifiable computation. In 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (pp. 253-270). IEEE.